Wikipedia is probably the most current, extensive, and accessible knowledge base available. Currently, there are over 10,000 Wikipedia entries for human genes of interest thanks to the Gene Wiki project and the contributions of the dedicated and altruistic Wikipedia community. Unfortunately, many of these articles are out-of-date or are just stubs in desperate need of content. If you are in science and truly believe in open access, why not contribute?

It may be a bit intimidating to edit a scientific Wikipedia article if you’ve never done it before, but it is actually quite easy! In the interest of encouraging wiki contributions from those in STEM disciplines, here’s a 10 step walk-thru for editing a Wikipedia entry:

1. Register/Login – No, it’s not necessary for you to do this step in order to edit a wiki, but you should just so you can be proud of all the wiki pages you improve in the future

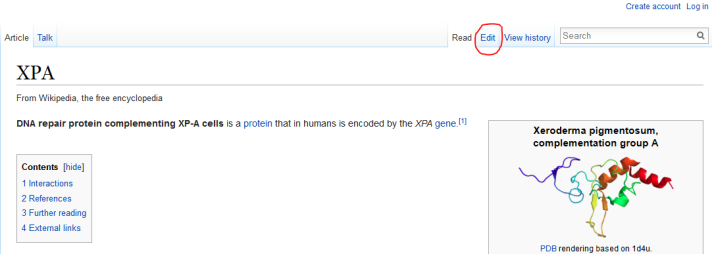

2. Go to a wiki page in need of an update. Look up your favorite gene in wikipedia and help improve it!

3. Click on the ‘edit’ tab in the top, right corner of the page

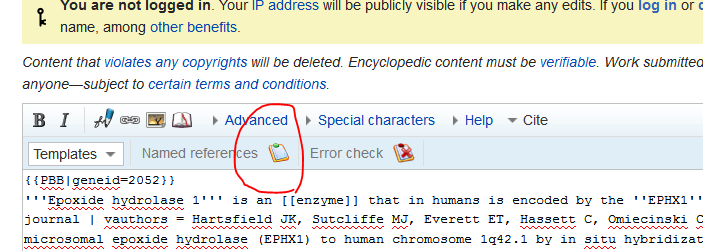

4. Edit the content of the page. To add a section break, use double equal signs (eg- ==Section== )

5. To add a journal reference, click on ‘cite’ in the navigation bar, click on the ‘templates’ drop-down menu and select ‘cite journal’. Enter the PMID of the article into the ‘PMID’ field and click on the search (magnifying glass) icon to auto-populate the other fields.

![]()

6. If you plan on using this reference more than once, assign it a reference name so you can insert it again later.

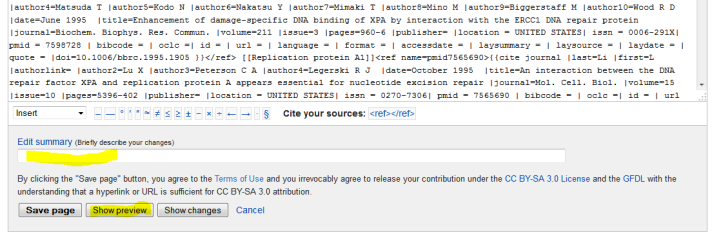

7. Click ‘insert’ to insert the reference

8. When using a previously inserted/named reference again just use the ‘Named Reference’ (clipboard) icon.

9. Make a note about your changes in the ‘edit summary’ field, and then preview (optional) and save your edits.

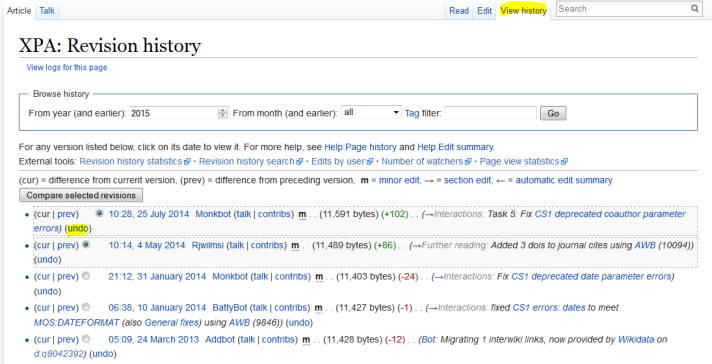

10. If you make a mistake, you can easily revert the edits you made. Just go to the ‘view history’ tab. Find the changes you need to revert and click ‘undo’.

That’s it! What are you waiting for?

Need more editing tips? Check out the Gene Wiki portal and learn more ways to help improve Wikipedia as a knowledge base for human genes of interest.